Sigmoidal Curve of Attractiveness

Tags:

I’m currently writing a post on why I disagree when people suggest that physical attractiveness is completely irrelevant in considering a partner / SO. Not that it trumps other qualities, just that it is, and should be, important. In explaining my reasoning, I realized that I should first publish this post, which I was inspired to write months ago by a discussion with some of my best friends. Look for the followup post called “Beauty is Common” in a few days, I’ll post a link in the comments section below (update: Beauty is Common).

Basically, my friends and I occasionally have fun discussing how we’ve defined our “attractiveness scale.” I imagine this isn’t a terribly uncommon topic among college-aged males in general; every time a debate is sparked about whether [pick a celebrity] is a “9” or a “10,” there is a lot of ambiguity regarding what those numbers really mean. As far as I know, there is no pan-gender consensus on the “right” way to assign numbers.

Preliminary Assumptions

- To clear the air of an unavoidable objection, is the possibility that two individuals could be using the exact same scale, criteria, etc. and simply have a discrepancy in the attractiveness of a third party. At this point, the only recourse is to uproariously declare the superiority of your assessment. No way dude!. 7.5?! You’re crazy. Definitely a 9. Not a very satisfactory outcome. I think this is why we frequently entertain the possibility that we’re using a different metric.

- It’s almost always necessary for both parties to agree that they’re discussing purely physical attractiveness by doing their best to ignore other factors that heavily influence overall attractiveness. For example, if evaluating a common friend, things like shared values, interests in common, or sense of humor may influence you to adjust your numerical rating. Money or fame could make you bump up or down your rating. Because confounding variables like interests and the importance of personality factors may not be compatible with those with whom you’re having the discussion, it’s critical to come to an agreement that the discussion at hand should not include these factors. Otherwise you’ll be comparing apples and melons. I mean oranges.

Scales

One of the first points of disagreement is in the type of scale that’s used. For example,

- What is the range of the scale?

Common options include:- 0–10

- 1–10

- 1–100

- What are the definitions of the endpoints of the scale?

Best or worst looking person you…- have ever met.

- have ever seen in person.

- have ever seen (media included).

- could possibly imagine.

- What is the increment of the scale?

- Integers

- Halfs

- Continuous

- What is the type of scale?

- Linear

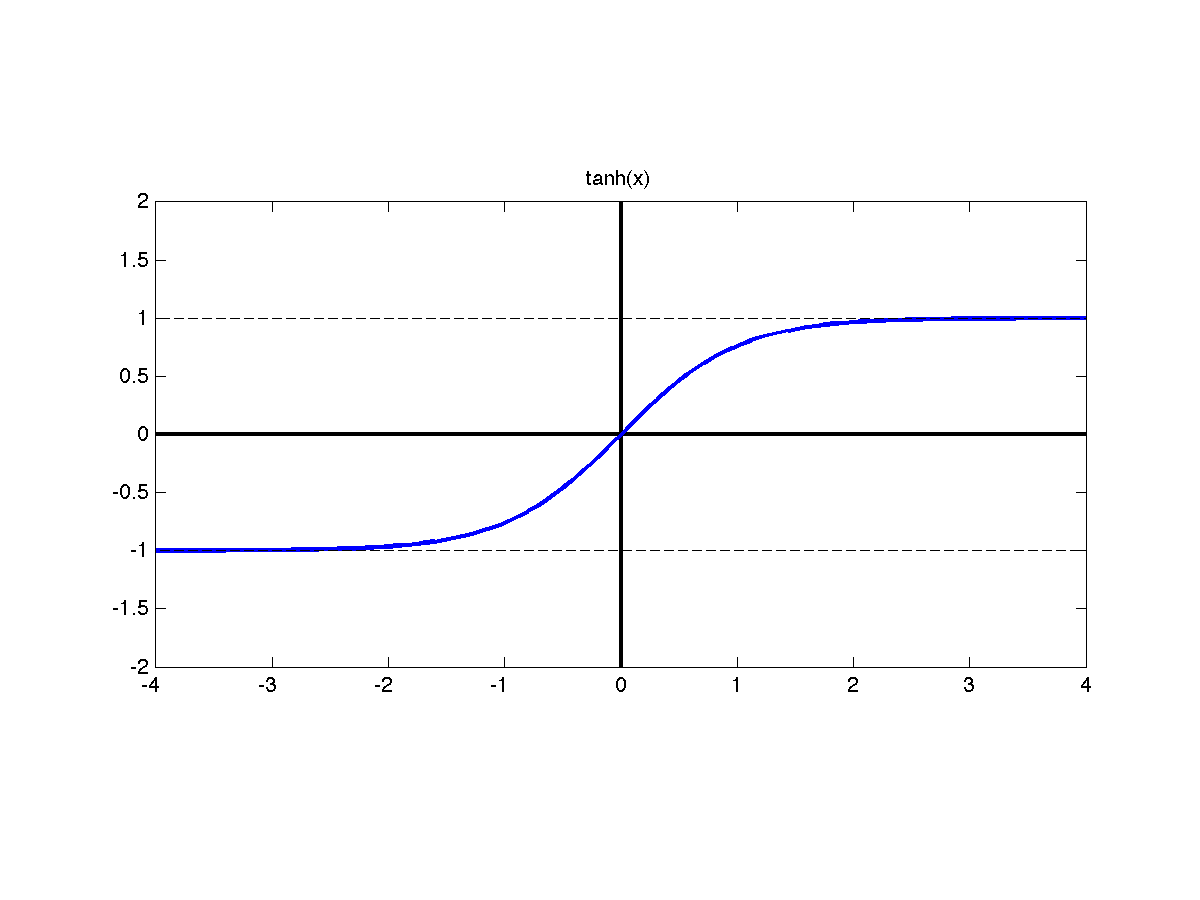

- Some kind of hyperbolic tangent or asymptotic sigmoidal curve

- Bell curve

Discussion Points

- Range

- In my experience, most people use 1 to 10, and I’m fine with that.

- Endpoints

- This is always a point of contention.

- I tend to use the best looking person I’ve seen in person to avoid discussions about airbrushing or photoshopping. Also, I lack imagination.

- Increment

- I generally use integers, although this is problematic for my preferred “type” of scale, as discussed below.

- If you find the granularity of integers to be too coarse and prefer a half-point increment, fine, but in that case why don’t you just use a 20 point scale and use integers?

- A continuous scale is probably most appropriate, but makes for tedious discussion (7.023 vs 7.024), so I discourage its use.

- Type

- This will exceed the capacity of a properly employed bulleted list. See below.

Linear

A person that believes in a linear scale holds that the difference in attractiveness between any two sequentially ranked individuals is the same as the difference between any other two. In other words, the difference between a “2” and a “4” is the same as the difference between an “8” and a “10.” While this type of scale may work for some, it just doesn’t feel right to me.

For example, let’s say that you are a single, 29 year old, heterosexual male, and by this point in your life you have your linear conceptual model of attractiveness pretty well set. You sit down at a café and are enjoying a cinnamon bun when the most incredibly attractive woman you’ve ever seen walks by your table. In fact, she’s so attractive, that she’s more attractive than anyone you’d ever imagined, and at least 150% as attractive as your previously heralded “10.” Your world just got flipped upside down. If she’s linearly 150% of your previous 10, that makes her a 15. Because a 10 is the highest possible score, you then need to scale down everyone you’ve ever seen to match your new “all time record.” Remember that high school girlfriend you thought was a 7? Cross-multiply and divide. She is now a (7/15) * 10 = 4.67. We’ll round up to 5, both to be generous and to comply with your integer increment standard. She didn’t seem like a 5, and you don’t think of her as a 5, but this is what extreme outliers do to a linear scale adherent. Alternatively, if you ran across someone you found significantly more repulsive than any individual you’d previously seen, would everyone else suddenly shift up a few numbers? Would it suddenly make you want to date that physically plain person that you’d considered a 4 for so long, since he or she’s now a 6?

Asymptotic

I’ll be brief here. If this word doesn’t make sense, click: Asymptote. These individuals basically hold that the highest and lowest numbers are reserved for someone so attractive or unattractive that they might as well not exist, and although new individuals may *approach* that standard, they won’t ever reach it. On one hand, this helps avoid the quandary of having to redefine one’s scale (and therefore previous or current SOs) based on new information. On the other hand, this forces your hand into choosing imaginary (or perhaps potential) endpoints. As I wrote earlier, I don’t have enough imagination for endpoints that I haven’t seen. This shape of curve does have some benefits, though, which I’ll discuss in the next section.

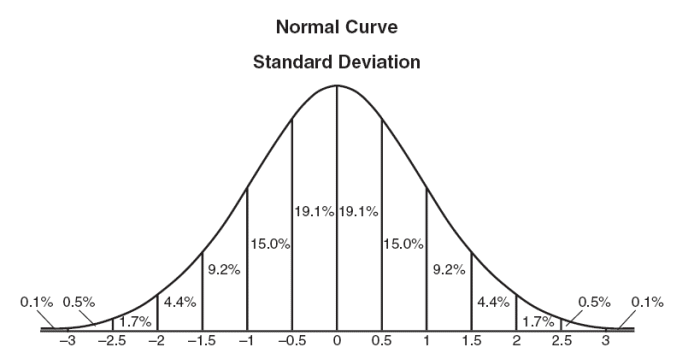

Bell Curve

Let’s have a quick lesson on normal distributions. Here’s the wikipedia article, and here’s a site that provides a good overview of a normal distribution, including the image below.

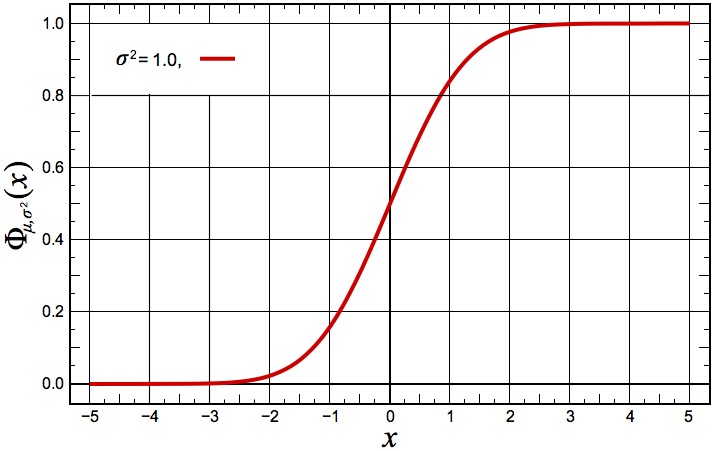

The main idea as relevant to this post is that when you take a populational cross-section of a continuous variable such as height, shoe size, or affinity for pickles, you tend to find that “most people” fall somewhere in the middle, duh, with a decreasing proportion of the population as you approach either extreme. Unfortunately, I don’t really remember what a standard deviation is (something like the average of the absolute values of the difference between the components of a set and its mean), or how it relates to a bell curve. I do remember that scoring “2 standard devs above the mean” on an exam means you’re doing well. If you converted the standard bell curve into a chart of “percentage of a population that is at or below the curve at a given SD,” the result might look something like this.

The interesting part about this is the middle part of the “S curve.” If you’ll notice, the slope of the function is especially steep at this point, what we might define as a “5.” What this means to me is that this is where a very “average” looking person might find themselves, but this is also the place at which small changes in their attractiveness have the potential to make the biggest differences in where they sit in relation to the rest of the population. In other words, if you’re an average looking person, this is where you’ll get the biggest bang for your buck for improving your looks, but also pay the largest penalty when you slack off. According to this model, at least.

This is a big part of the reason that I think the “bell curve” model is the best representation of the real world, or at least my experience of the world. How many times have you seen an average looking person start hitting the gym, get a haircut, change their wardrobe, and suddenly start catching your attention? It makes a huge difference. Contrast that to someone that is already at an 8 or 9. The same degree of change typically won’t bump them up or down much. This is the problem with using an integer increment, as mentioned earlier. People at the far ends of the scale may make observable changes that simply aren’t sufficient for a whole number change. I don’t know of a good solution to that predicament. Even when you run into them at 7:30 in the morning at Walgreens when they’ve got a cold, obviously unshowered, and wearing the same sweats for the third day in a row… they still look pretty darn good if they were a true 8 or 9 in the first place. Reciprocally, if they aspire to ever get a me++ on their number, it’s not going to be a piece of cake. Pun intended.

###

Summary

- Guys occasionally divulge in shallow, trite conversation.

- Take precautions against engaging a nerdy guy in such conversation, or you might be subjected to tedious, preposterous attempts at quantification and algorithmization.

- If you think your number is <3 or >7, relax. Learn Italian. Pick up a new hobby. You’re probably not going very far.

- If you think you’re within ~1 SD of the mean… don’t waste your potential, you have the most to gain!

Look for my followup post, “Beauty is Common,” in the comments section below. Should be up in a couple of days.